Next tours: See Walks & Tours: “The Pre-Raphaelites” or “The Great Art Treasures of Manchester”.

Meet: Art Gallery.

“What in the world do you want with art in Manchester? Why can’t you stick to your cotton spinning?” That was the impolite response from William Cavendish, seventh Duke of Devonshire, when asked by the organisers of the 1857 Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition for a loan of paintings from his copious collection.

“What in the world do you want with art in Manchester? Why can’t you stick to your cotton spinning?” That was the impolite response from William Cavendish, seventh Duke of Devonshire, when asked by the organisers of the 1857 Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition for a loan of paintings from his copious collection.

The exhibition took place between the Botanical Gardens in Old Trafford and the railway (now Metrolink). A catalogue of around 16,000 works – sculpture, metalwork, ceramics, jewellery, paintings by Michelangelo and Rembrandt – was arranged to show the world that Manchester was about more than smoking chimneys, cotton spinning and making money; that it could be a home of culture as well.

Its eventual legacy was to convince the Corporation to take over the Royal Manchester Institution, Charles Barry’s Classical revival building of 1827-35, and convert it into the city art gallery, re-opening in 1882. The new Art Gallery Committee bought enthusiastically and accumulated an impressive collection topped by Ford Madox Brown’s monumental Work, bought for £400 on the recommendation of Manchester Guardian editor C. P. Scott.

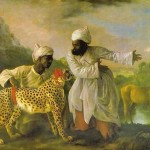

The creation of the Art Fund in the 1960s allowed galleries to save for buying major works. Manchester obtained Baccicio’s St John the Baptist and Stubbs’ Cheetah and Stag. In 1979 the Assheton-Bennetts donated a collection of 17th century Dutch and Flemish paintings, and in 1993 Sidney Bernstein, founder of Granada TV, bequeathed a collection that included works by Chagall and Modigliani.

The creation of the Art Fund in the 1960s allowed galleries to save for buying major works. Manchester obtained Baccicio’s St John the Baptist and Stubbs’ Cheetah and Stag. In 1979 the Assheton-Bennetts donated a collection of 17th century Dutch and Flemish paintings, and in 1993 Sidney Bernstein, founder of Granada TV, bequeathed a collection that included works by Chagall and Modigliani.

But it is the remarkable collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings that the gallery is best known. William Holman Hunt’s The Scapegoat, The Shadow of Death and The Hireling Shepherd would grace any collection. The tour looks at these, the Lowry and Valette collection, and 20th century works by Bacon, Bomberg and Sickert.

* The relationship between the gallery and Manchester politicians has not always been fruitful. One Lord Mayor, pointing to the paintings at a function in the early 20th century, was heard saying to a VIP: “None of your manufactured stuff, lad. Real masterpieces there, and all ’and-painted.” But that was nothing compared to the alderman sat next to the Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt at the opening of the gallery in summer 1883 who scribbled a note to a colleague that read: “Who or what is a Holman hunt (sic)?”