Next tour: Dates to be set.

Meet: tbc.

Booking: Please have your tickets ready for the inspector.

To book privately (ideal for railway enthusiasts): please e-mail info@newmanchesterwalks.com.

Some time around 600 BC a railway called the rutway was built in ancient Greece to move boats from the builder’s yard to the sea across the Isthmus of Corinth. It took another two thousand years or so before the world’s first proper passenger line opened, and it did so in Manchester.

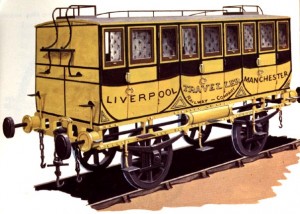

That line opened in 1830 and connected Manchester to Liverpool. Only the Manchester terminus – Liverpool Road – still stands; it is now part of the Science and Industry Museum. Although there had been earlier railways the Liverpool and Manchester line was the first with two tracks, timetables and stations. And what a story developed as the line took shape!

Constructing a railway line to connect the two cities as a way of overcoming problems caused by the freezing of the canals in winter had first been discussed in 1822. A public company was formed in 1824, but attempts to push a Bill through Parliament were thwarted. A Miss Byrom and a Mrs Atherton who owned the land around Liverpool Road objected to the siting of the station, while Lord Derby and Lord Sefton who owned the land further west, hired a gang of heavies to hound the surveyors, which led to George Stephenson in turn engage a prize fighter to protect his men.

Not that the railway entrepreneurs’ survey was too clever. The Old Quay Canal Company, which feared for the commercial future of their River Irwell work should the railway open, claimed correctly that the surveyors had made a number of inaccurate calculations such as placing the Irwell 30 feet above Vauxhall Road even though it lay 5 feet below. The Bill was withdrawn and resubmitted more successfully in 1826.

Once work started the railway builders discovered major physical problems that needed to be overcome along the 31-mile route, particularly in Chat Moss, the huge tract of swampy land near Warrington. More than 70,000 square yards of spoil were tipped into one part of the moss without success. Eventually young larch trees from Botany Bay Woods were laid together herring-bone style to solidify the land. A different kind of problem came with the construction of the Sankey Viaduct over a canal. Nine arches, each 50 feet wide, were needed to take the line across.

Originally the railway company contemplated using horse-drawn carriages, but as these would have only been able to reach a maximum speed of 15 mph the idea was dropped in favour of steam locomotives. Trials were held at Rainhill to choose an engine, and George Stephenson’s Rocket was considered the best. There were also animalian considerations. Summoned before a Parliamentary committee in 1825, George Stephenson was asked: “Suppose now, one of these engines to be going along railroad at the rate of nine or ten miles an hour, and that a cow were to stray upon the line and get in the way of the engine, would that not, think you, be a very awkward circumstance?”, to which the engineer memorably replied: “Aye, very awkward indeed for the coo.”

At first only one station between the cities was planned, half way, at Newton le Willows. This was later changed so that there would be a Manchester terminus, but originally the line was meant to end in Salford without the crossing the Irwell. Such a location would have been too far from Manchester so a station was built on what is now Liverpool Road. With no prototype for how a station should look, the building took the form of a typical late Georgian terrace. There were two entrances – for First and Second Class; Third Class just went round the back – and a brick property on the corner adapted as the Station Agent’s house. As for travellers starting from other towns, it was announced that passengers standing alongside the line could signal to the driver if they wanted the train to stop by waving a handkerchief or umbrella, an option no longer available.

At first only one station between the cities was planned, half way, at Newton le Willows. This was later changed so that there would be a Manchester terminus, but originally the line was meant to end in Salford without the crossing the Irwell. Such a location would have been too far from Manchester so a station was built on what is now Liverpool Road. With no prototype for how a station should look, the building took the form of a typical late Georgian terrace. There were two entrances – for First and Second Class; Third Class just went round the back – and a brick property on the corner adapted as the Station Agent’s house. As for travellers starting from other towns, it was announced that passengers standing alongside the line could signal to the driver if they wanted the train to stop by waving a handkerchief or umbrella, an option no longer available.

Everything was ready for the first run on 15 September 1830. The two cities were agog. Passengers marvelled at the idea of travelling between the two cities in just over hour, rather than over much of the day, even though medical men had warned potential passengers of the dangers travelling at high speeds might have on their health. Some 700 people crammed into eight special trains for the opening journey while a crowd of around 50,000 stood at various points alongside the line to watch. Henry Booth, the railway company’s treasurer, was particularly excited. “From west to east and from north to south, the mechanical principle, the philosophy of the nineteenth century, will spread and extend itself. The world has received a new impulse. The genius of the age, like a mighty river of the new world, flows onwards, full, rapid and irresistible.”

Fourteen years later a new station was built further north by Chetham’s. The new queen gave permission for it to be called Victoria. Soon Manchester was at the centre of this remarkable new form of transport. New Manchester Walks’ “World’s 1st Railways” walk tells this story in all its triumphant glory.