Next tour: 2024.

Eventually …

Eventually …

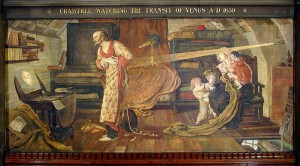

Ed Glinert or John Alker will unveil the stories behind these masterpieces, describing the background to each, explaining who sat for the main characters, relating just how much politics went into the choice of the stories chosen and bring the murals to life, inter-twining them with the history of the city and England.

The story of the Ford Madox Brown Town Hall Murals is one of the most remarkable in the city. The curious viewer who enters the Great Hall looks at the Ford Madox Brown paintings Murals and asks: why these scenes, why this version of history?

The 12 panels contain a palette-full of stories but also a catalogue of twists. It seems perverse to find a panel illustrating the baptism of a king that never came to Manchester but not of the Peterloo Massacre. It seems strange to find a mural of an Oxford cleric, tried for heresy at London’s St Paul’s, but nothing about the opening of the world’s first railway station in Manchester.

Here’s another odd thing; a series of paintings decorating a room that ranks as the crowning creation of Victorian Gothic revival architecture and design contains no Victorian stories among them.

These are amongst the greatest art treasures not just of Manchester but of Victorian painting. Read on, below the pic, to discover more.

Take a good look at the 5th Panel: “The Trial of Wycliffe”. This is taster of what we tell you about just this one painting, that shows the depth of our research.

John Wycliffe was the leading religious scholar in England in the late 14th century. An adviser to the king, Edward III (whose statue stands on the Town Hall’s Princess Street façade), he would journey with the monarch to discuss religious affairs with the Pope at Avignon. But during the 1370s Wycliffe began to fear that the church had lost its way – that it had become corrupted by money. He denounced clerical corruption and began preaching the simple message of Jesus by preaching peripatetically barefoot.

Wycliffe founded a group of lay preachers who became known as the Lollards (a Dutch word meaning “mumbler”). They wanted to bring the word of God to people directly, verbally, which was their only option in the days before the printing press was invented. As part of this campaign he began to translate the Bible (from Latin) into English, the first major figure to do so. This was a revolutionary move as it threatened to break the stranglehold priests had over the Old and New Testaments, then only available in Latin, which few outside their closed circle could understand. Ironically Wycliffe could only deal with the Latin, as he knew no Hebrew or Greek, the Bible’s original languages.

On 19 February 1377 (exactly 500 years before the Town Hall was ready to open) Wycliffe was summoned before William Courtenay, Bishop of London, as Ford Madox Brown depicts, “to explain the wonderful things which had streamed forth from his mouth”. The trial was set to take place in St Paul’s Cathedral, London, but was abandoned when the mob, thinking that they heard John of Gaunt threatening the Bishop of London, caused such a riot the trial was abandoned.

A few months later the Pope issued five bulls condemning Wycliffe’s writings. In 1382 all his works were banned and he was summoned for trial again, this time at Blackfriars Monastery in London. Just as the proceedings began the courtroom shook. A violent earthquake had hit London. The trial was abandoned with both sides claiming it to be an omen supporting their stance.

Wycliffe retired to Leicestershire and died of natural causes in 1384, having avoided the gallows and stake, unlike so many religious polemicists throughout history. The contemporary historian Thomas Walshingham was pleased with Wycliffe’s demise. He wrote how “John Wycliffe, that instrument of the devil, the enemy of the Church, the confusion of men, the idol of heresy, the mirror of hypocrisy, the nourisher of schism, was by the rightful doom of God smitten with a horrible paralysis [before he] breathed out his malicious spirit in to the abodes of hell.”

But the death did not bring an end to the drama. In 1428 the Pope ordered that Wycliffe’s bones be exhumed and destroyed. The dust was thrown into the River Swift, but it was Wycliffe’s supporters who claimed victory. They explained how as the River Swift flows into the River Avon which flows into the River Severn which flows into the Bristol Channel which flows into the Atlantic Ocean, Wycliffe’s message – of religious independence – was now spreading throughout the world.

The Church was unable to prevent the flow of Wycliffe’s ideas, and Rome now permits the Bible to be translated into languages other than the (non-original) Latin.

•••

In the painting the hero is being supported by his powerful patron, John of Gaunt, Earl Palatine of Lancaster, son of Edward III and Philippa (seen in the 4th Mural), the royal figure nominally in charge of Manchester, which is the main local connection. John of Gaunt’s wife is trying to restrain him from injuring Wycliffe with his sword. At Wycliffe’s side is Lord Percy who points to Wycliffe’s books. The five unfriendly looking friars are Wycliffe’s counsel. Geoffrey Chaucer, to the right of John of Gaunt, is taking notes. Further right William Courtenay (the standing bishop) is whispering in the ear of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury.

Ford Madox Brown featured a full selection of local figures and friends as inspiration for the faces. Wycliffe is modelled by Frederic Shields, the local artist who was originally going to share the murals with Brown. John of Gaunt is Harold Rathbone, a pupil of Brown. Constance of Castile, Duchess of Lancaster, wearing the bright red dress, is Mrs Henry Boddington. Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, the seated bishop, is the Town Hall organist Dr James Kendrick Pyne. William Courtenay, the standing bishop, is Brown himself.